View all posts

If you want to be notified about future posts, please consider subscribing:

In 3D graphics a typical perspective projection matrix takes, as one of its arguments, the vertical field of view. As an example have a look at DirectX’s D3DXMatrixPerspectiveFovLH function.

In video games, quite often the wider the aspect ratio of the rendering resolution, the wider the horizontal field of view [1]. Some games (first person games) often go as far as to allow players to configure field of view to their liking. So it turns out that in practice we more often than not need to work with the horizontal field of view, and not the vertical field of view that most perspective matrix math is based on. As such, it is convenient to have functions with which we can convert vertical field of view to horizontal and vice versa.

At first I thought these formulas would be easy. I thought that to convert from the vertical field of view to horizontal all we need to do is to multiply the vertical field of view by the screen’s aspect ratio. It’s a little bit more complicated than that.

1. Math Formulas

Let’s go straight into the formulas for conversion. Derivation of those formulas is presented in the next section.

On input we need the screen’s aspect ratio .

We also denote the vertical field of view as and horizontal field of view as

.

Now, given the vertical field of view the formula for horizontal field of view

is:

The opposite, given the horizontal field of view the formula for vertical field of view

is:

2. Derivation of the Formulas

Derivation of the formulas we start off with an illustration of the view frustum:

The view frustum has the tip, which is the point where the camera/eye is located. Distance away is the near plane, and distance

away is the far plane. Typically all triangles that are within the frustum’s bounds (the grey area) are projected onto the near plane and that is what ends up being displayed to the viewer.

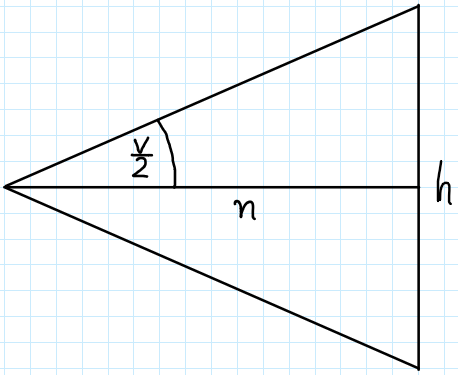

Let’s now have a look at the side section of the frustum:

What we are seeing in this image is only the part from the eye to the near plane — to the left there is the eye and to the right, next to letter “h” is the near plane. Actually, the letter “h” denotes the near plane’s height .

Other variables in this image are the distance to the near plane and half of the vertical field of view’s angle

.

We can tie all these variables together with the following equation:

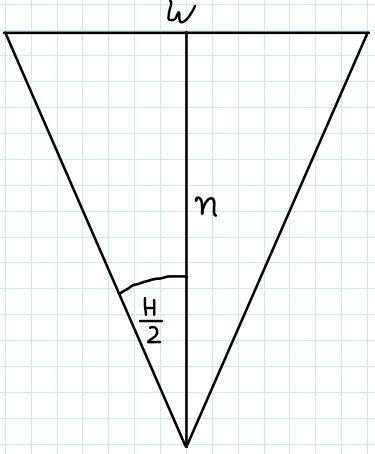

Now let’s have a look at the frustum’s top section (birdseye view):

This one is similar but now instead of the height we have the near plane’s width and instead of the vertical field of view’s half-angle we have the horizontal’s

.

Equation that ties all these variables is:

We now have two equations that both sport the same variable in them. Slight manipulation of these equations leads to:

We can now write:

This equation ties together the vertical field of view and horizontal field of view

. Assuming we know the near plane’s width

and height

we can now easily calculate

as a function of

(and vice versa):

This formula requires us to know the near plane’s width and height

. Note though that we actually only need the ratio of those values, not the values themselves, and that ratio will be constant throughout the entire view frustum (and beyond). So we don’t actually need the exact near plane size, we only need the ratio

which we can calculate from the application window’s width and height for example. This leads us to the final formula:

Derivation of the formula for follows the same pattern.

3. Example Application

On GitHub you can find an example application demonstrating the above formula in action.

Here’s C# source code implementing the formulas:

private float MyVerticalToHorizontalFieldOfView(float fovY, float aspect)

{

fovY *= Mathf.Deg2Rad;

float fovX = 2.0f * Mathf.Atan(aspect * Mathf.Tan(fovY / 2.0f));

return fovX * Mathf.Rad2Deg;

}

private float MyHorizontalToVerticalFieldOfView(float fovX, float aspect)

{

fovX *= Mathf.Deg2Rad;

float fovY = 2.0f * Mathf.Atan(1.0f/aspect * Mathf.Tan(fovX / 2.0f));

return fovY * Mathf.Rad2Deg;

}

The functions above assume that the vertical and horizontal field of views, fovX and fovY are given in degrees and that the output values are also in degrees. Functions Mathf.Tan and Mathf.Atan oparate in radians hence the need for a few conversions.

In function Update of the Unity script we have:

void Update()

{

float aspect = (float)Screen.width / (float)Screen.height;

float fovY = Camera.main.fieldOfView;

float fovX;

fovX = Camera.VerticalToHorizontalFieldOfView(fovY, aspect);

fovY = Camera.HorizontalToVerticalFieldOfView(fovX, aspect);

Debug.Log("Unity's: " + fovY + " " + fovX);

fovX = MyVerticalToHorizontalFieldOfView(fovY, aspect);

fovY = MyHorizontalToVerticalFieldOfView(fovX, aspect);

Debug.Log("My: " + fovY + " " + fovX);

}

In this code we first read the camera’s (vertical) field of view and calculate the aspect ratio. Then, we convert the vertical fov (field of view) to horizontal and then back to vertical (we should end up with the same value we started with).

The conversion is carried out using two different sets of functions — first with Unity’s built-in functions and then with our implementations. This way we can confirm that our implementations work correctly.

4. Bibliography

[1] Field of view in video games, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_of_view_in_video_games